|

Táboriták, árvák, kelyhesek |

|

|

| A Szent Korona pólyában | |||

| A két Hunyadi János | Magyarok cseh földön | ||

| Ki volt Brandeisi Giskra János? | Csehek Magyar földön | ||

| A Losonc melletti csata 1451-ben | A Huszita Biblia | ||

| Mátyás király elsö hadjárata | |||

| A Vak Vezér (Jan Zizka) | |||

| Vissza a föoldalra | |||

|

|

|||

|

|

|

||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

A térkép nagyítása rákattintással Forrás: www.sigismundus.hu

|

|||

|

Európai keresztes háborúk a husziták ellen

Az 1420-1434 között zajló csehországi fegyveres harcok, az ún. huszita háborúk ideológiai alapját Husz János prágai prédikátor és elődje, John Wycliffe angol teológus egyházi tanításai teremtették meg.

John Wycliffe (1820-1864)

Husz, Wyclif elveit továbbfejlesztve radikális reformokat sürgetett a katolikus-és a cseh egyházban egyaránt. Írásaiban, prédikációiban a Szentírás nemzeti nyelven való hirdetését, a két szín alatti áldozást, a kolostorok megszüntetését és a papi kiváltságok eltörlését szorgalmazta. Hogy eretneknek minősített nézeteit tisztázza, Luxemburgi Zsigmond magyar és cseh király menlevelével megjelent a konstanzi zsinaton,(1414-18) ahol a zsinat Zsigmond ígéretével szemben elfogatta és máglyára küldte. Husz halála nyomán hatalmas felháborodás tört ki szerte Csehországban, amely nem csupán a katolikus egyház vagy a király ellen irányult, hanem erős függetlenségi és németellenes arculattal is rendelkezett. Ez időben ugyanis zömében német nemzetiségűek alkották a király legfőbb támaszát jelentő főurak, nagypolgárság és a főpapság csoportjait. Ezen kívül a cseh nyelvet nem ismerték el hivatalos nyelvnek, viszont a német nyelv a latinnal egyenrangú szerepet töltött be az oktatásban és a bürokráciában egyaránt. Csehországban először a prágai óvárosi 'Falhozépült Szent Márton templom'-ban vezették be a két szín alatti áldozást, és megkezdődött a huszita mozgalom. A nemzeti felkelés 1419. július 30-án tört ki a Jan Zelivsky prédikátor által vezetett 'szegények menetével'.

A 'Falhozépült Szent Márton templom', ami a nevét onnan kapta, hogy a városfal 'keetévágta', így a templom egyik fele a prágai Ó-Város, míg a másik fele az Új-Város területére esik.

Az első, még egymástól elszigetelt fegyveres

megmozdulások ugyanebben az évben robbantak ki szerte Csehországban. A fegyveres

felkelések erejét Zsigmond először a helyi királyi várak zömében német

nemzetiségű helyőrségével próbálta meg leveretni, miután azonban ez a kísérlete

kudarcot vallott, más megoldást választott: 1420. márciusában keresztes

hadjáratot hirdetett a csehországi eretnekség ellen. Zsigmond döntése azért

volt rendkívül szokatlan, mert keresztes hadjárat címmel korábban jobbára a

Szentföldre, ill. a török terjeszkedés megállítására szervezett hadjáratokat

illeték. Zsigmond lépése azonban politikailag indokoltnak mondható, mivel a huszitizmus rendkívüli gyorsasággal ütötte fel a fejét Lengyelországban és a német területeken egyaránt, így érthető, hogy a király rövid idő alatt nagy haderőt akart mozgósítani a huszita eretnekség kigyomlálására.

A huszita elnevezés alatt nem az egész cseh népet,

vagy Csehországot kell értenünk, mivel a csehek nem álltak egységesen a mozgalom

mögé, az ország német lakossága pedig túlnyomó részben Zsigmond pártján foglalt

állást. A mozgalom két fő ágból állt: a zömében parasztok és kispolgári elemek

alkotta radikális táboritákból, akik az egyházi hatalommal és a világi

intézményekkel fordultak szembe, másrészről a módos polgárság és a nemesség nagy

része által támogatott, mérsékelt kelyhesekből. A két irányzat 1420-ban lépett

szövetségre egymással Prágában, melynek eredményeképp jött létre az ún. prágai

kompaktátum, amely a mozgalom alapvető célkitűzéseit tartalmazta. Ebben

megtiltották a papok vagyonosodását és befolyásukat a világi ügyekben, a

hívőknek engedélyezték a két szín alatti áldozást és a szentmisék nemzeti

nyelven való megtartását is.

Zsigmond 1420-1431 között öt keresztes hadjáratot

szervezett és vezetett Csehországba. Ez a példa is jól mutatja a huszitákkal

szemben kifejtett erőfeszítés nagyságát, amely azonban nem vezetett eredményre.

V. Márton pápa (1417-31) bűnbocsánatot ígérő bulla kiadásával állt a hadjárat

ügye mellé. A pápa bullájában teljes bűnbocsánatot ígért a részt vevőknek, de

azoknak is, akik maguk nem tudván eljönni, más személyeket küldenek hadba saját

költségükön. A felhívásnak nagy hatása volt Európa-szerte, főleg német

területről, Morvaországból, Lengyelországból és Magyarországról érkezők adták a

keresztesek többségét, de még a távoli Aragóniából és Frankföldről is jelentős

had gyűlt Zsigmond zászlaja alá. Az első hadjárat (1421) kudarca után mind szélesebb tömegeket igyekeztek bevonni a husziták elleni harcba, Zsigmond pedig a kellő anyagi háttér megteremtését tűzte ki legfőbb céljául, ami a gyakorlatban a még a kezében lévő cseh egyházi vagyon elzálogosítását jelentette. E lépés következményeként a háború lezárásakor az egyházi javak túlnyomó része (beleértve a templomok felszereléseit is) világi kézbe került.

Az öt hadjárat során előfordult, hogy európai

mértékkel is kivételes erejű seregek indultak meg a husziták ellen, egyes

esetekben még a legmegbízhatóbb források is 100 ezres hadakról szólnak, de nem

ritka a 200 ezres sereg említése sem.

A második keresztes hadjárat során (1421-22)

Skandinávia és Itália kivételével Európa minden tájáról érkeztek csapatok,

hadjáratuk mégis eredménytelen maradt. A huszita háborúk korai szakaszában még a támadás volt a keresztesek fő célja, várak ostromával és nyílt csaták kezdeményezésével próbálkoztak, az első kudarcok után azonban már arra is volt példa, hogy a keresztes hadak csatát sem vállalva futamodtak meg a közelgő ellenség hírére. E rendkívüli sikerek titka az elszántságban és a hadászati újításokban rejlett.

A husziták harci technikájának alapja nem volt új

keletű Európában, mégis ők fejlesztették tökélyre azt a módszert, amellyel majd

egy évtizeden keresztül sikeresen ellenálltak minden ellenséges támadásnak.

Taktikájuk alapja a szekerek harci eszközként való alkalmazása volt. E megoldás

alkalmazása már az ókorban is bevett gyakorlat volt, ám ott általában támadó

céllal használták őket, ugyanakkor az ellenkezőjére is volt példa. Védelemben

való első alkalmazásuk a Római birodalomra törő barbár népeknél fordult elő.

Szekérváraikkal győzték le a római légiókat a gótok 378-ban Hadrianapolisznál,

és ugyancsak szekérvárakat alkalmaztak a rómaiak és a hunok egymás ellen

451-ben, a catalaunumi csatában.

A husziták első meghatározó vezére, Jan Zizka volt az, aki 1420-ban, egy kilátástalannak tűnő csata közben végső megoldásként állította hadrendbe a csapatait kísérő kocsisort. A zseniális hadvezér a szekereket kör formát képezve szorosan egymás mellé állította, rájuk pedig lándzsákkal és dárdákkal felfegyverzett embereket rakatott. A sebtében összetákolt szekérvárból kiálló lándzsák mint a sündisznó megannyi tüskéje meredtek a támadó lovasok felé. Ziskra ötletét siker koronázta, innentől fogva ezt az eljárást mind gyakrabban, és mind több újítással együtt vetették be az összecsapások során. Hamarosan minden sereget felszereltek ún. harci szekerekkel, amelyeknek oldalait vastag deszkákkal erősítették meg, kocsisnak pedig olyan képzett irányítókat választottak, akik a legnehezebb helyzetben is ügyesen kormányoztak.

Jan Zizka Prágában, a legnagyobb lovas szobor a világon

A szekérvárak a csaták alatt általában magaslati pontokon foglaltak helyet, kettős körgyűrűt alkotva. A kocsikat puskásokkal, lándzsásokkal, parittyásokkal rakták meg, az egyes kocsik közti réseket pedig ágyúkkal töltötték ki. A szekérvár alkotta gyűrűn kívül foglalt helyet a huszita könnyűlovasság, amely vész esetén azonnal képes volt visszavonulni az erődítmény belsejébe, hogy után belülről védekezhessen a támadó ellenséggel szemben. A körgyűrű belsejébe gyakran íjászokat telepítettek, akik a közeledő ellenség sorait biztos fedezék mögül voltak képesek megtizedelni.

A szekérvár azonban nem csak stabil védelmet

jelentett a katonaság részére, hanem jelentős támadó erőt is képviselt. A

kocsikat gyorsan mozgásba tudták hozni, amelyek az ütközetek során gyakran

félkörívet alkotva támadták oldalba az ellenfél seregtestjeit, majd összezárulva

ejtették csapdába az ellenséget.

Több csatában is előfordult, hogy a magaslatra

települt huszita sereg a szekereit kövekkel vagy gyúlékony anyaggal rakta meg,

és a hegyoldalon felfelé felkapaszkodó katonaság sorai közé gurították őket.

A háború sorsát azonban nem csupán a nyíltmezei

csaták döntötték el, az egyes, fallal körülvett városok bevétele mindkét fél

számára nagy kihívást jelentett. A csehek meglepő hatékonysággal alkalmazták a

még gyerekcipőben járó tüzérséget, nagy hangsúlyt fektetve ágyúparkjuk

fejlesztésére és hatékony használatára. Ennek ellenére az egyes várak ostrománál

a fő ostromgép még mindig a katapult maradt, amellyel köveket, tüzes golyókat és

még sok más dolgot, többek között emberi ürüléket lőttek a falakon belülre.

Karlstein 1422-es ostromakor a támadók például 9032 romboló kő mellett mintegy

1822 hordónyi emberi ürüléket, megközelítőleg a sereg teljes ''természetes

hulladékát'' lőtték ki a városra. A szekérvárak alkalmazása azonban nem egyedüli magyarázata a husziták győzelmeinek. Okként hozható fel az erős, néhol fanatizmusba torkolló vallási háttér, a másik oldalon viszont a keresztes hadak sokszínűsége és az irányításukat zavaró érdekellentétjeik. Ki kell emelni a cseh hadak gyors mozgathatóságát, amely főleg az állandó gyakorlatozásnak és nagyfokú fegyelemnek volt köszönhető. Ezzel szemben az európai hadseregek ráérős lassúsággal mozogtak és több alkalommal is előfordult, hogy amikor az ellenségnek a saját területén kellett védelmeznie egy várost, a huszita hadak a városhoz kirendelt védősereget megelőzve szállták meg az adott települést.

A közel másfél évtizeden át dúló harcok folyamán

hatalmas pusztítást szenvedett el a néhány évtizeddel korábban Európa egyik

leggazdagabb országának számító Cseh Királyság. Mind emberben, mind anyagban a

veszteségek óriásiak voltak. A háborús viszonyok közepette a földmívesek nem

vetettek, így aratni sem volt mit. A belső források elapadtak,

Husz János követői rablókká vedlettek át. A cseh

hadak nem egy alkalommal feldúlták Sziléziát, Morvaországot, a német

területeket, de eljutottak Magyarországra is. 1428-tól fogva szinte minden évben

betörtek hazánkba, 1432-ben elfoglalták Nagyszombatot, 1433-ban pedig

Körmöcbányát prédálták fel. A nehezen mozgósítható nemesi felkelés nem vehette

fel a versenyt a gyorsan mozgó cseh hadakkal szemben. Ám a huszitáknak is volt

gyenge pontja. Miközben egyre nagyobb sikereket értek el külhonban, belső

egységük annál látványosabban bomlott.

Zizka, a csehek nagy, veretlen hadvezére 1424-ben Přibyslav városának ostroma közben halt meg pestisben. Az utolsó éveiben teljesen megvakuló férfi pótolhatatlan űrt hagyott maga után. Halála után megszűnt a hadak egységes vezetése, kiéleződött a taboriták és a kelyhesek közötti ellentét is. A huszita seregek vezetői közül Nagy-és Kis Prokop emelhetők ki, teljes egységet azonban nekik sem sikerült teremteniük. 1426-ban és 1431-ben (Domazlice) még jelentős győzelmeket sikerült aratniuk a betörő hadak felett, de sikereiknek lassan bealkonyult. Vereségüket nem az ellenség túlereje, hanem annak konszenzust kereső politikája okozta. 1433 novemberében Prágában egyezség jött létre a huszitizmus mérsékelt szárnyát alkotó kelyhesek és a katolikus egyház között. Az egyház elfogadta a prágai kompaktátumot, cserébe a kelyhesek elismerték a pápát a huszita egyház fejéül. A megbomlott mozgalomban a radikális táboriták magukra maradtak, és 1434. május 30-án Lipany mellett végzetes vereséget szenvedtek a már kelyhesekkel is kiegészült királyi seregektől.

A huszita mozgalom veresége nem jelentette automatikusan az általuk kifejlesztett harcmodor bukását. A cseh zsoldosok még több évtizeden keresztül rendkívül keresettek voltak Európa hadseregeiben, mások viszont önállósították magukat. Az Erzsébet özvegy királyné hívására Győrbe jövő Giskra zsoldosvezér például szabályos kiskirályságot hozott létre a Felső-Magyarországon, amellyel még Hunyadi János sem bírt el. A cseh zsoldosok továbbra is rendkívüli harcértékükről voltak híresek, viszont a szekérvárak kora leáldozóban volt. Használták még őket 1444-ben a várnai és 1448-ban a rigómezei csatában is, de immáron kevés sikerrel. A gyorsan fejlődő, és szervezetten használt tüzérség ekkorra már képessé vált a mozgó erődítmények megállítására. Forrás: An-no online történelmi magazin, http://www.an-no.hu

Képsorozat

Jan Zizka, a vakon is verhetetlen Jan ika z Trocnova a Kalicha (c1360 - 1424)

Jan Zizka, teljes nevén Jan ika z Trocnova a Kalicha, a huszita háborúk első felének hadvezére, cseh köznemes család sarja, született Trosznovban (Budweis környékén) 1360., meghalt Przsibiszláv várának ostromlása közben 1424 október 11.-én. Gyermek korában félszemére megvakult. Mint ifjú Vencel király udvarában került, azután a német lovagrend zászlója alatt a lengyelek és litvánok ellen harcolt és részt vett az 1410-iki tannenbergi csatában. Majd Zsigmond király alatt Magyarországban a törökök ellen küzdött, mire kalandvágya Franciaországba vitte, ahol az angolok soraiban a franciák ellen harcolt és az Azincourt melletti csatában jelen volt.

Jan Zizka a grünwaldi (tannenbergi ) csatában. Jana Matejka festménye. A kép jobb oldalán, az előtérben, a kardjával lesújtani készülő páncélos harcos Jan Zizka.

Husz János kivégeztetése után a huszita mozgalomhoz csatlakozott és vitézségével meg hadvezéri tehetségeivel annyira magára vonta a husziták bámulatát, hogy vezérüknek ismerték el. Az ő kezdeményezése folytán kezdtek a husziták a kimagasló pontokon táborokat építeni és a szekérvár alkalmazásában is nagy ügyességre tettek szert. Első diadalát Vitkov hegyén aratta, melynek megerősített ormáról a keresztes hadnak rohamait 1420 júliusában fényesen visszaverte. November elsején Pankracnál győzte le Zsigmond királyt és nyomban rá Viehrad várát szállotta meg Prága közbelében. Itt több ágyút kerített hatalmába, melyeknek azután jó hasznát vette. Huszinesz Miklós halála után (1421) valamennyi huszita párt elismerte őt fővezérének. Nemsokára azonban, Raby várának ostromlása közben, nyíllövés következtében másik szemén is megvakult. Ezt követően kis kocsin vitette magát csapatai után és főbb embereinek útbaigazítása mellett vezényelt a csatákban. Mellette gombamódre nőttek ki a tehetséges alvezérek: tanítványai éppen a vakságának köszönhetően sajátították el a vezér tudományát. Zizka ugyanis - szekerén ülve - a legapróbb részletességgel beszámoltatta tisztjeit a környékről, az ellenség elhelyezkedéséről, és eszerint, hangosan gondolkodva adta meg utasításait. Környezete így valóságos hadiiskola volt. Innen került ki a két Prokop, a külföldön híressé vált Ladvenko, Zeleny, Vitovec vagy a nálunk tartományúri hatalmát kiépítő Jan Giskra is. 1422-ben Kutná Hora közelében ismét hatalmas vereséget mért Zsigmondra, aki több ezer embert vesztett és saját életét is csak bajosan tudta megmenteni. Azután benyomult Morvaországba és Alsó-Ausztriába, hol hadai rettenetesen garázdálkodtak. Midőn arról értesült, hogy a prágaiak az engedelmességet megtagadták, váratlanul a város előtt termett és megtörte a dacos polgárságot (1424). Hasztalan iparkodott Zsigmond király Zizkát a maga pártjára vonni: Zizka rá sem hallgatott és a neki felajánlott helytartóságot sem fogadta el. Javában folytatta a háborút, midőn Przsibiszláv város ostromlása közben (Csaszlau közelében) a táborban dühöngő pestis őt is elragadta. Halála annyira felbőszítette fanatikus hadait, hogy a várost rohammal bevették, felégették és lakóit egy szálig lekaszabolták. Zizka összesen 13 nagyobb és 100 kisebb ütközetből került ki mint győztes; egyetlen egyszer, Kremsier táján húzta a rövidebbet. Ellenfelei és a hagyomány szörnyű dolgokat meséltek hajmeresztő bosszújáról és kegyetlenségeiről. Tetemét saját parancsára Csaszlauban temették el és óriási buzogányát sírja fölé helyezték. Amíg csak tartott a husziták háborúja, Jan Zizka vitézei "árváknak" nevezték magukat. Elfogadták ugyan az új, kiváló hadvezérek parancsnokságát, de mindvégig Jan Zizka maradt az "árvák" vezetője, az ő szellemében harcoltak tovább. II. Ferdinánd császár parancsára azonban a sírt lerombolták és Zizka csontjait kihányták. 1874. az ifjúcsehek Przsibiszláv mellett nagy szobrot emeltek Zizka emlékének. Később Prágában, első nagy győzelmének színhelyén hatalmas emlékművet emeltek, ami a világ legnagyobb vezért ábrázoló lovas szobra. Forrás: A Pallas Nagy Lexikona

Nagy vagy Kopasz Prokop, a pap vezér

Prokop Holý, magyarul Prokopius András, a Nagy vagy a Kopasz, a legszélső irányú huszita vezér. Nagybátyja neveltette s vele beutazta Francia-, Spanyol- és Olaszországot, sőt Jeruzsálemet is. Haza érkezvén pappá avattatott és a huszita háború kitörése után Ziska kapitánya lett. Miután Zizka (1424) és Schwambergi Bohuszláv (1425) halála után a husziták egyik pártja, a táboriták vezérré választották, Ausztriát pusztította el, az aussigi csatában (1426 jún. 16.) egy meisseni-szász-türingi hadsereget semmisített meg és a várost felgyújtotta. Azt követően, hogy az osztrákokat Morvaországból kiűzte, 1427 tavaszán Ausztriát a Dunáig elpusztította. Időközben a táboriták egy másik csapatja, az úgynevezett árvák, Prokupek vagy Kis Prokopius alatt a Lausitzba hatolt és Laubant elégette. Ezekkel együtt fosztogatta Prokopius Sziléziát. Miután a németek Oroszországba hatoltak, az ostromolt Miest felszabadította, a német hadsereget megverte és azután Tachaut ostrommal bevette. Majd Szilézián és Morvaországon keresztül Pozsonyig hatolt. 1429-1430-ban elpusztította a Lausitzot, Meissent, Szász-, Morvaországot és Sziléziát. A következő évben egy német birodalmi kereszteshadat, mely Taust ostromolta, megfutamított (1431 augusztus 14.). Alvezére, a Kis Prokopius erre Albert osztrák herceget Morvaországból kiűzte, Prokopius maga pedig a szászokat Csehországból, amire Sziléziába és Kis Prokopius-szal együtt Magyarországba hatolt a Vág folyóig, de visszaveretvén, 1432. Lausitzot és Brandenburgot az Odera melletti Frankfurtig elpusztította. Visszaszorították ugyan őket, de csakhamar Sziléziát és Szászországot új portyázó hadjáratok által nyugtalanították. A prágai szerződéseknek a két Prokopius a táboritákkal és árvákkal együtt nem akarta magát alávetni, és a kelyhesek elleni elkeseredett harcban végre a Cseh-Brod melletti lipanyi döntő csatában teljesen megverettek, s ott Prokopius el is esett. Forrás: A Pallas Nagy Lexikona

Origins

The Hussite movement assumed a revolutionary character as soon as the news of the execution of Jan Hus by order of the Council of Constance(6 July 1415) reached Prague. The knights and nobles of Bohemia and Moravia, who were in favour of church reform, sent to the council at Constance (2 September 1415) a protest, known as the protestatio Bohemorum, which condemned the execution of Hus in the strongest language. The attitude of Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor, who sent threatening letters to Bohemia declaring that he would shortly drown all Wycliffites and Hussites, greatly incensed the people. Troubles broke out in various parts of Bohemia, and drove many Romanist priests from their parishes. Almost from the first the Hussites divided into two groups, though many minor divisions also arose among them. Shortly before his death Hus had accepted a doctrine preached during his absence by his adherents at Prague, namely that of Utraquism, or the obligation of the faithful to receive communion in both kinds (sub utraque specie). This doctrine became the watchword of the moderate Hussites known as the Utraquists or Calixtines, from the Latin calix (the chalice), in Czech kaliníci (from kalich); while the more extreme Hussites soon became known as the Taborites (táborité), named after the city of Tábor that became their centre; or Orphans (sirotci) a name they adopted after the death of their beloved leader and general Jan ika. Under the influence of his brother Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor, King Wenceslaus IV of Bohemia endeavoured to stem the Hussite movement. A certain number of Hussites led by Nicolas of Hus no relation of Jan Hus, though of the same town left Prague. They held meetings in various parts of Bohemia, particularly at Sezimovo Usti (not to be confused with Usti nad Labem), near the spot where the town of Tábor was founded soon afterwards. At these meetings they violently denounced Sigismund, and the people everywhere prepared for war. In spite of the departure of many prominent Hussites the troubles at Prague continued. On 30 July 1419, when a Hussite procession headed by the priest Jan Zelivsky marched through the streets of Prague, anti-Hussites threw stones at the Hussites from the windows of the town-hall of the new town. The people, headed by Jan ika, threw the burgomaster and several town-councillors, who had instigated this outrage, from the windows (the first "Defenestration of Prague"), whereupon the crowd killed them immediately. On hearing this news King Wenceslaus succumbed to an apoplectic fit, and died a few days afterwards (16 August 1419).

The outbreak of fighting

The death of the king resulted in renewed troubles in Prague and in almost all parts of Bohemia. Many Romanists, mostly Germans for they had almost all remained faithful to the papal cause suffered expulsion from the Bohemian cities. In Prague, in November 1419, severe fighting took place between the Hussites and the mercenaries whom Queen Sophia (widow of Wenceslaus and regent after the death of her husband) had hurriedly collected. After a considerable part of the city had been destroyed, the parties declared a truce on 13 November. The nobles, who though favourable to the Hussite cause supported the regent, promised to act as mediators with Sigismund, while the citizens of Prague consented to restore to the royal forces the castle of Vysehrad, which had fallen into their hands. ika, who disapproved of this compromise, left Prague and retired to Plzen. Unable to maintain himself there he marched to southern Bohemia, and after defeating the Romanists at the battle of Sudomer (25 March 1420) in the first pitched battle of the Hussite wars, he arrived at Usti, one of the earliest meeting-places of the Hussites. Not considering its situation sufficiently strong, he moved to the neighbouring new settlement of the Hussites, called by the biblical name of Tábor. Tabor soon became the centre of the advanced Hussites, who differed from the Utraquists by recognizing only two sacraments - Baptism and Communion - and by rejecting most of the ceremony of the Roman Church. The ecclesiastical organization of Tabor had a somewhat puritanical character, and the government was established on a thoroughly democratic basis. Four captains of the people (hejtmane) were elected, one of whom was ika; and a very strictly military discipline was instituted.

Depending on the terrain, Hussites prepared carts for the battle, forming them into squares or circles. The carts were joined wheel to wheel by chains and positioned aslant, with their corners attached to each other, so that horses could be harnessed to them quickly, if necessary. In front of this wall of carts a ditch was dug by camp followers. The crew of each cart consisted of 18-21 soldiers: 4-8 crossbowmen, 2 handgunners, 6-8 soldiers equipped with pikes or flails (the flail was the Hussite "national weapon"), 2 shield carriers and 2 drivers. The Hussites' battle consisted of two stages, the first defensive, the second an offensive counterattack. In the first stage the army placed the carts near the enemy army and by means of artillery fire provoked the enemy into battle. The artillery would usually inflict heavy casualties at close range. In order to avoid more losses, the enemy knights finally attacked. Then the infantry hidden behind the carts used firearms and crossbows to ward off the attack, weakening the enemy. The shooters aimed first at the horses, depriving the cavalry of its main advantage. Many of the knights died as their horses were shot and they fell. As soon as the enemy's morale was lowered, the second stage, an offensive counterattack, began. The infantry and the cavalry burst out from behind the carts striking violently at the enemy - mostly from the flanks. While fighting on the flanks and being shelled from the carts the enemy was not able to put up much resistance. They were forced to withdraw, leaving behind dismounted knights in heavy armor who were unable to escape the battlefield. The enemy armies suffered heavy losses and the Hussites soon had the reputation of not taking captives.

The first anti-Hussite crusade

After the death of his childless brother Wenceslaus, Sigismund had acquired a claim on the Bohemian crown, though it was then, and remained till much later, in question whether Bohemia was an hereditary or an elective monarchy. A firm adherent of the Church of Rome, Sigismund was successful in obtaining aid from Pope Martin V, who issued a bull on 17 March 1420 which proclaimed a crusade for the destruction of the Wycliffites, Hussites and all other heretics in Bohemia". Sigismund and many German princes arrived before Prague on 30 June at the head of a vast army of crusaders from all parts of Europe, largely consisting of adventurers attracted by the hope of pillage. They immediately began a siege of the city, which had, however, soon to be abandoned. Negotiations took place for a settlement of the religious differences. The united Hussites formulated their demands in a statement known as the Four Articles of Prague". This document, the most important of the Hussite period, ran, in the wording of the contemporary chronicler, Laurence of Brezova, as follows: 1. The word of God shall be preached and made known in the kingdom of Bohemia freely and in an orderly manner by the priests of the Lord. 2. The sacrament of the most Holy Eucharist shall be freely administered in the two kinds, that is bread and wine, to all the faithful in Christ who are not precluded by mortal sin - according to the word and disposition of Our Saviour. 3. The secular power over riches and worldly goods which the clergy possesses in contradiction to Christs precept, to the prejudice of its office and to the detriment of the secular arm, shall be taken and withdrawn from it, and the clergy itself shall be brought back to the evangelical rule and an apostolic life such as that which Christ and his apostles led. 4. All mortal sins, and in particular all public and other disorders, which are contrary to Gods law shall in every rank of life be duly and judiciously prohibited and destroyed by those whose office it is. These articles, which contain the essence of the Hussite doctrine, were rejected by Sigismund, mainly through the influence of the papal legates, who considered them prejudicial to the authority of the Roman see. Hostilities therefore continued. Though Sigismund had retired from Prague, the castles of Vysehrad and Hradcany remained in possession of his troops. The citizens of Prague laid siege to the Vysehrad (see Battle of Vysehrad), and towards the end of October (1420) the garrison was on the point of capitulating through famine. Sigismund attempted to relieve the fortress, but was decisively defeated by the Hussites on 1 November near the village of Pankrác. The castles of Vysehrad and Hradcany now capitulated, and shortly afterwards almost all Bohemia fell into the hands of the Hussites.

The second anti-Hussite crusade

Internal troubles prevented the followers of Hus from fully capitalising on their victory. At Prague a demagogue, the priest Jan Zelivsky, for a time obtained almost unlimited authority over the lower classes of the townsmen; and at Tabor a communistic movement (that of the so-called Adamites) was sternly suppressed by ika. Shortly afterwards a new crusade against the Hussites was undertaken. A large German army entered Bohemia and in August 1421 laid siege to the town of Zatec. After an unsuccessful attempt of storming the city, the crusaders retreated somewhat ingloriously on hearing that the Hussite troops were approaching. Sigismund only arrived in Bohemia at the end of the year 1421. He took possession of the town of Kutná Hora but was decisively defeated by Jan ika at the battle of Nemecky Brod (Deutschbrod) on 6 January 1422.

Civil war

Bohemia was for a time free from foreign intervention, but internal discord again broke out, caused partly by theological strife and partly by the ambition of agitators. Jan elivský was on 9 March 1422 arrested by the town council of Prague and decapitated. There were troubles at Tábor also, where a more advanced party opposed ika's authority. Bohemia obtained a temporary respite when, in 1422, Prince Sigismund Korybut of Poland (nephew of King Ladislaus II Jagiello of Poland) briefly became ruler of the country. He was a governor sent by duke Vytautas of Lithuania (brother of the King of Poland), who accepted the Hussite proposal to be their new king. His authority was recognized by the Utraquist nobles, the citizens of Prague, and the more moderate Taborites. Korybutovic, however, remained a short time in Bohemia, as in 1423 he was called to come back to Lithuania, after Jagiello had made a treaty with Sigismund. On his departure, civil war broke out, the Taborites opposing in arms the more moderate Utraquists, who at this period are also called by the chroniclers the "Praguers", as Prague was their principal stronghold. On 27 April 1423, ika now again leading, the Taborites defeated the Utraquist army under Čeněk of Wartenberg at the battle of Horic; and shortly afterwards an armistice was concluded at Konopilt.

The third anti-Hussite crusade

Papal influence had meanwhile succeeded in calling forth a new crusade against Bohemia, but it resulted in complete failure. In spite of the endeavours of their rulers, Poles and Lithuanians did not wish to attack the kindred Czechs; the Germans were prevented by internal discord from taking joint action against the Hussites; and the King of Denmark, who had landed in Germany with a large force intending to take part in the crusade, soon returned to his own country. Free for a time from foreign aggression, the Hussites invaded Moravia, where a large part of the population favoured their creed; but, paralysed again by dissensions, they soon returned to Bohemia. The city of Hradec Králové, which had been under Utraquist rule, espoused the doctrine of Tabor, and called ika to its aid. After several military successes gained by ika in 1423 and the following year, a treaty of peace between the Hussites was concluded on 13 September 1424 at Liben, a village near Prague, now part of that city.

Campaigns of 1426 and 1427

In 1426 the Hussites were again attacked by foreign enemies. In June of that year their forces, led by Prokop the Great - who took the command of the Taborites shortly after ika's death in October 1424 - and Sigismund Korybutovic, who had returned to Bohemia, signally defeated the Germans at Usti nad Labem. After this great victory, and another at the Battle of Tachov in 1427, the Hussites repeatedly invaded Germany, though they made no attempt to occupy permanently any part of the country.

Polish and Lithuanian involvement

From 1421 to 1427 the Hussites received military support from the Poles. Poland, though a devoutly Catholic nation, was supporting the Hussites on non-religious grounds. Poland's motive was revenge against Germany for the Polish-Lithuanian-Teutonic War (1409-1411). Because of this, Jan ika arranged for the crown of Bohemia to be offered to Jagiello, the King of Poland, who, under pressure from his own advisors, refused it. The crown was then offered to Grand Duke Vytautas of Lithuania and Vytautas accepted it, with the condition that the Hussites reunite with the Catholic Church. In 1422, ika accepted the Polish king's nephew, Sigismund Korybut, as regent of Bohemia for Vytautas. Korybut never managed to return the Hussites to the Catholic Church; and he even had to resort to force of arms when dealing with the various factions. Korybut did not tolerate the Protestant rebels breaking their promise of reuniting with the Catholic Church. On a few occasions, he even fought against both the Taborites and the Oreborites to try to force them into reuniting. Large scale Polish involvement was ended in 1427 when Korybut was arrested by the Hussites after Polish plans to hand over the Hussite forces to Emperor Sigismund were discovered. The Poles, however, did not really want to withdraw; the only reason they did is because the Pope planned to call a crusade against Poland if they did not.

Beautiful rides

Spanilé jízdy, or beautiful rides, as the Hussites called them, were undertaken in many different foreign lands. Throughout the Hussite Wars, especially under the leadership of Prokop the Great, invasions were made into Silesia, Saxony, Hungary, Lusatia, and Meissen. Every raid that the Hussites carried out was against a country that had supplied the Germans with men during the anti-Hussite crusades. These raids were made to try to strike enough fear in these areas to make sure that they would not help out the Germans again. However, the raids did not have the desired effect; these countries kept supplying soldiers to the crusade against the Hussites. During yet another war between Poland and the Monastic State of the Teutonic Knights, some Hussite raiders helped the Poles. In 1433, a Hussite army of 7000 fighting men marched through Neumark into Prussia and captured Dirschau on the Vistula River. They would eventually reach the mouth of the Vistula where it enters the Baltic Sea near Danzig. There, they performed a great victory celebration to show that nothing but the ocean could stop the Hussites. The Prussian historian Heinrich von Treitschke would later write that they had "greeted the sea with a wild Czech song about God's warriors, and filled their water bottles with brine in token that the Baltic once more obeyed the Slavs."

Peace talks and renewed wars

The almost uninterrupted series of victories of the Hussites now rendered vain all hope of subduing them by force of arms. Moreover, the conspicuously democratic character of the Hussite movement caused the German princes, who were afraid that such views might extend to their own countries, to desire peace. Many Hussites, particularly the Utraquist clergy, were also in favour of peace. Negotiations for this purpose were to take place at the ecumenical council which had been summoned to meet at Basel on 3 March 1431. The Roman See reluctantly consented to the presence of heretics at this council, but indignantly rejected the suggestion of the Hussites that members of the Greek Church, and representatives of all Christian creeds, should also be present. Before definitely giving its consent to peace negotiations, the Roman Church determined on making a last effort to reduce the Hussites to subjection. On 1 August 1431 a large army of crusaders under Frederick, Margrave of Brandenburg, whom Cardinal Cesarini accompanied as papal legate, crossed the Bohemian border and on 14 August the crusaders reached the town of Domalice. Upon the arrival of the Hussite army reinforced with some 6000 Polish hussites and under the command of Prokop or as the legend has it upon seeing the Hussite banners and hearing their battle hymn "Kdo jsou Boí bojovníci" ("Ye Who are Warriors of God"), the crusaders immediately took to flight. On 15 October the members of the council, already assembled at Basel, issued a formal invitation to the Hussites to take part in its deliberations. Prolonged negotiations ensued; but finally a Hussite embassy, led by Prokop and including John of Rokycan, the Taborite bishop Nicolas of Pelhrimov, the English Hussite Peter Payne and many others, arrived at Basel on 4 January 1433. It was found impossible to reach an agreement. Negotiations were not, however, broken off, and a change in the political situation of Bohemia finally resulted in a settlement. In 1434 war again broke out between the Utraquists and the Taborites. On 30 May of that year the Taborite army, led by Prokop the Great and Prokop the Lesser, who both fell in the battle, was totally defeated and almost annihilated at Lipany. An end to the Polish Hussite movement in Poland would arrive as well: the Polish Hussites, often reinforced by their Czech Slav brethren, had been raiding there for years, and the royal Polish forces under Władysław III of Varna would defeat the Hussites at the Battle of Grotniki, bringing the Hussite Wars to an end.

Peace agreement

The moderate party thus obtained the upper hand; and it formulated its demands in a document which was finally accepted by the Church of Rome in a slightly modified form, and which is known as the compacts. The compacts, mainly founded on the articles of Prague, declare that: I. The Holy Sacrament is to be given freely in both kinds to all Christians in Bohemia and Moravia, and to those elsewhere who adhere to the faith of these two countries. 2. All mortal sins shall be punished and extirpated by those whose office it is so to do. 3. The word of God is to be freely and truthfully preached by the priests of the Lord, and by worthy deacons. 4. The priests in the time of the law of grace shall claim no ownership of worldly possessions. On 5 July 1436 the compacts were formally accepted and signed at Jihlava, in Moravia, by King Sigismund, by the Hussite delegates, and by the representatives of the Roman Church. The last-named, however, refused to recognize as archbishop of Prague John of Rokycan, who had been elected to that dignity by the estates of Bohemia.

Aftermath

The Utraquist creed, frequently varying in its details, continued to be that of the established church of Bohemia 'til all non-Roman religious services were prohibited shortly after the Battle of the White Mountain in 1620. The Taborite party never recovered from its defeat at Lipan, and after the town of Tabor had been captured by George of Podebrady in 1452, Utraquist religious worship was established there. The Bohemian brethren, whose intellectual originator was Petr Chelčický but whose actual founders were Brother Gregory, a nephew of Archbishop Rokycan, and Michael, curate of Zamberk, to a certain extent continued the Taborite traditions, and in the 15th and 16th centuries included most of the strongest opponents of Rome in Bohemia. J. A. Komensky (Comenius), a member of the brotherhood, claimed for the members of his church that they were the genuine inheritors of the doctrines of Hus. After the beginning of the German Reformation many Utraquists adopted to a large extent the doctrines of Martin Luther and of John Calvin; and in 1567 obtained the repeal of the compacts, which no longer seemed sufficiently far-reaching. From the end of the 16th century the inheritors of the Hussite tradition in Bohemia were included in the more general name of "Protestants" borne by the adherents of the Reformation.

All histories of Bohemia devote a large amount of space to the Hussite movement. See: Count Lützow, Bohemia; an Historical Sketch (London, 1896) Frantiek Palacký, Geschichte von Bohmen Bachmann, Geschichte Bohmens L. Krummel, Geschichte der bohmischen Reformation (Gotha, 1866) L. Krummel, Utraquisten und Taboriten (Gotha, 187 i) Ernest Denis, Huss et la guerre des Hussites (Paris, 1878) H. Toman, Husitské válečnictví (Prague, 1898). Original text from 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hussite_Wars

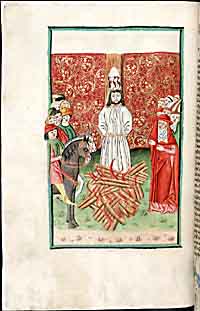

John Wycliffe csontjainak elégetése

|

|||

|

Írj!

|

|||

|

WebDesign: www.cassaauditor.hu

|

|||

|

|

|||